Mekelle፡Telaviv, Nairobi, Pretoria, London, (Horn News Hub).

Strengthening US–Somaliland Ties: A Historic Step Forward

The Republic of Somaliland has hailed the introduction of a new bill in the United States Congress that could mark a turning point in relations between the two nations. The bill, introduced by Republican Congressman Brian Mast, calls on the US Secretary of State to explore establishing a representative office in Hargeisa and to issue separate travel advisories for Somaliland.

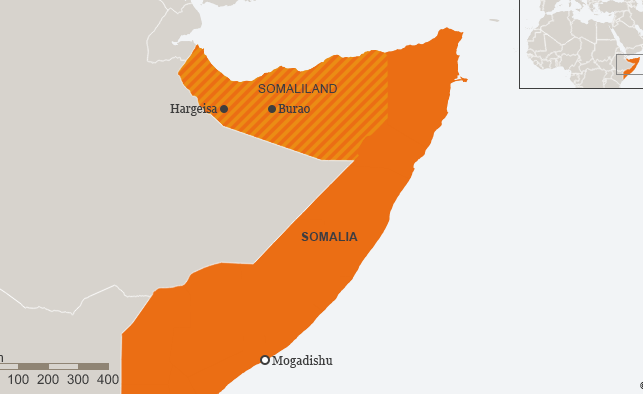

For Somaliland, which has operated as a de facto independent state for more than three decades but remains unrecognised internationally, the legislation is more than symbolic. It represents a rare acknowledgement from Washington of Somaliland’s distinct political and security achievements in one of the most volatile corners of the world.

Unlike war-torn Somalia, Somaliland has managed to maintain relative peace and stability since declaring independence in 1991. It has developed functioning democratic institutions, held competitive elections, and kept extremist groups at bay. This track record of stability in the Horn of Africa where piracy, terrorism, and state fragility dominate headlines has long bolstered Somaliland’s argument that it deserves international recognition.

The proposed US bill not only underscores these achievements but also signals a potential recalibration in how Washington engages with the region. By distinguishing Somaliland from Somalia, the legislation reflects the reality on the ground: two entities with fundamentally different governance and security trajectories.

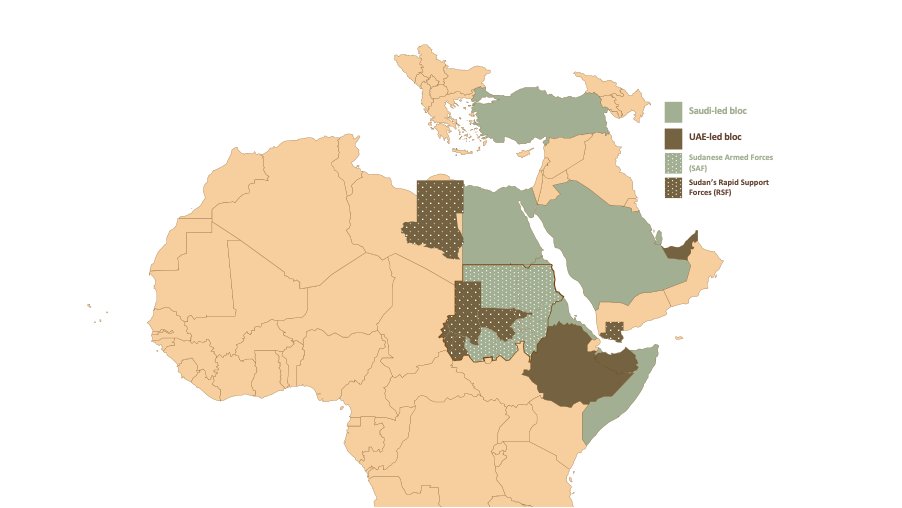

Supporters argue that deepening ties with Hargeisa is not simply a matter of fairness but also of strategic necessity. Somaliland’s location along the Gulf of Aden places it at the crossroads of global trade routes and near vital maritime chokepoints. As great power competition intensifies in the Horn of Africa—most notably China’s expanding influence—the US could find in Somaliland a democratic partner committed to rule of law and regional security.

Somaliland’s government has welcomed the move, describing itself as a “trusted partner for peace and security.” Officials point to the territory’s role in safeguarding maritime routes and building a resilient society in the absence of international recognition. For Hargeisa, the bill affirms that recognition is not merely a matter of justice but a strategic imperative both for Somaliland’s aspirations and for Washington’s long-term interests in Africa.

Critics, however, caution that any shift in US policy risks angering Mogadishu, which remains fiercely opposed to Somaliland’s quest for recognition. The African Union, too, has historically shied away from endorsing secessionist movements, wary of setting a precedent that could embolden other separatist claims across the continent.

Still, momentum appears to be growing. In recent years, Somaliland has forged closer ties with Taiwan, signed infrastructure and security agreements with the United Arab Emirates, and drawn attention from European partners. The introduction of a US bill however preliminary suggests that Washington is also beginning to reassess its long-standing Somalia-centric policy.

For Somalilanders, this moment represents cautious optimism. For the United States, it is a test of whether principles of democracy and stability can outweigh the inertia of diplomatic orthodoxy.

As the debate unfolds in Congress, one thing is clear: Somaliland is no longer on the periphery of US foreign policy. It has entered the conversation as a potential partner in a region where trusted allies are few and strategic stakes are high.