Mekelle/Tel Aviv/Nairobi/Pretoria/London

Finding Faith in Nature: How Waaqeffannaa Resonates Beyond Religion

By Selam Gebremedhin

In an era of growing secularism and shifting spiritual landscapes, the question of what makes us moral remains as alive as ever. Across generations and continents, people are re-examining the roots of faith, asking whether ethics depend on divine law or arise naturally from human conscience. For Selam, a young writer and thinker, the answer revealed itself not in a sacred book or temple, but in the quiet company of trees and rivers.

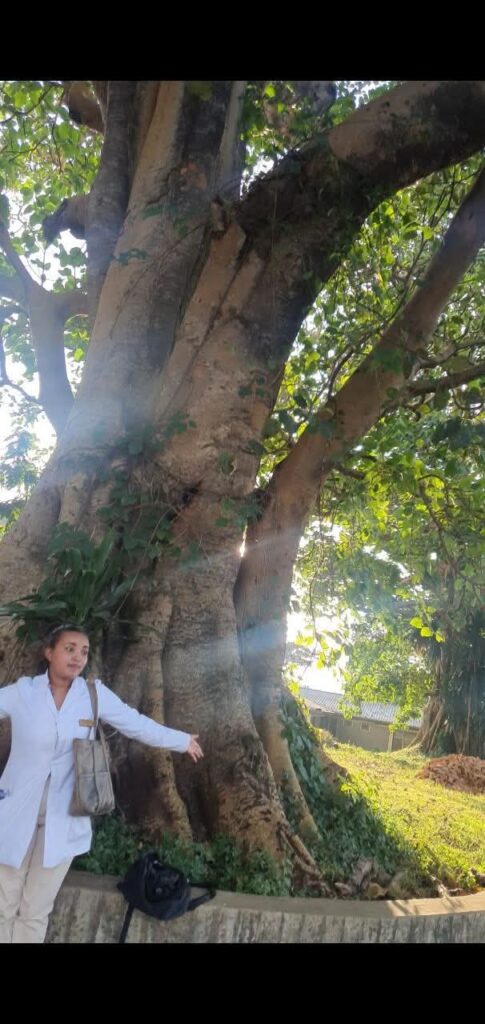

Selam describes herself simply as “a girl who hugs a tree for grounding.” For years, she debated with her theist friends about whether belief in God is necessary to live ethically. “I’ve always felt that people know right from wrong not because they read a holy book, but because their souls know it,” she wrote in an essay reflecting on her journey. “Morality isn’t learned from rules on paper it’s written in our hearts.” That idea that goodness is instinctive and universal shaped her worldview long before she found a tradition that seemed to affirm it.

Her discovery came when she encountered Waaqeffannaa, the traditional faith of the Oromo people of Ethiopia. One of the oldest monotheistic belief systems in Africa, Waaqeffannaa centers on Waaq, the one Creator who exists in all things rivers, mountains, forests, and skies. It teaches that human beings are endowed with both reason and a spiritual essence called ayyaana, guiding them to live ethically and in balance with creation. The world itself, believers say, is a living text, filled with divine signs for those who pay attention.

For Selam, learning about Waaqeffannaa was less a conversion than a recognition. “It felt like a homecoming,” she explained. “I had spent years studying different philosophies, searching for peace in faraway ideas, and then I realized something similar already existed in my own culture.” Before discovering Waaqeffannaa, she had been drawn to the teachings of the Indian mystic Sadhguru, whose emphasis on mindfulness, stillness, and awareness had inspired her to spend quiet evenings watching the sunset or feeling the wind on her skin. Those meditative practices, she later realized, mirrored the reverence for nature and consciousness that Waaqeffannaa had long embodied.

What struck her most about Waaqeffannaa was its absence of scripture. The faith has no holy book, no fixed commandments, no rigid hierarchy. Instead, it encourages followers to look to the world itself for guidance to the sunrise that teaches renewal, the flowing river that teaches persistence, and the changing seasons that teach patience and impermanence. “The sun rises and sets, a calf knows to nurse, seasons shift in rhythm all of it reflects God’s wisdom,” she wrote. “Life itself is enough to guide us.”

In a time when religion often feels defined by dogma and division, Waaqeffannaa offers a radically simple view of divinity: that the moral order is visible in the order of nature. Its followers see every act of kindness, every balance maintained, and every life nurtured as evidence of the divine. “To honor Waaq,” one practitioner told local media during a recent Irreecha celebration, “is to live in harmony with what Waaq has made.”

The most important expression of this belief is Irreecha, an annual thanksgiving festival held at rivers and lakes to celebrate peace, life, and abundance. Communities gather to give thanks to Waaq, to sing, dance, and bless one another with water. Though Selam has not attended Irreecha herself, she connects deeply with its essence. “When I sit by a river, hug a tree, or watch a bird land on a branch, I feel the same gratitude,” she said. “Those ordinary moments feel sacred.”

Irreecha has also become a powerful symbol of cultural revival for the Oromo people. Once marginalized under successive regimes, Waaqeffannaa and its practices are increasingly recognized as vital expressions of indigenous philosophy and identity. The festival now draws thousands each year, merging spirituality with cultural pride and environmental awareness. In a world facing ecological crises, its message gratitude and harmony with nature feels particularly urgent.

Selam’s discovery of Waaqeffannaa also echoes a broader global movement toward non-institutional spirituality.

Across generations, particularly among younger people, there is a quiet shift away from organized religion toward more personal, experiential forms of faith. Surveys by the Pew Research Center show that more individuals now identify as “spiritual but not religious,” finding meaning in meditation, nature, or ancestral traditions rather than formal creeds. For many, the divine is not distant or hierarchical, but immanent present in every moment of awareness.

In that sense, Waaqeffannaa speaks a universal language. Its moral framework centered on reason, balance, and gratitude aligns with ecological ethics, mindfulness movements, and indigenous philosophies across the world. Like Taoism, it sees harmony as the highest virtue. Like many Native American traditions, it honors the Earth as a living relative, not a resource to be exploited. For Selam, this universality is what makes it so profound: “It’s both ancient and modern at the same time,” she said. “It doesn’t tell you what to believe. It reminds you how to see.”

Her journey raises an enduring question where do we find our sacred moments? Are they in temples, prayers, and scriptures, or in the small acts of awareness that connect us to the living world? For Selam, the sacred is not confined to ritual. It reveals itself in the rustle of leaves, the rhythm of waves, the warmth of sunlight after rain. It is found not in words, but in presence.

As she puts it: “When I hug a tree, I feel grounded not just to the earth, but to something eternal.” In her story, faith becomes less about doctrine and more about recognition a quiet understanding that the divine has always been near, written not in books, but in the language of life itself.