Mekelle/Tel Aviv/Nairobi/Pretoria/London

“Assab Was Administered from Wollo”: Abadula Gemeda’s Reminder and Ethiopia’s Enduring Case for Maritime Access

By Contributor

Ethiopia’s debate over access to the sea is deeply anchored in state history, administrative continuity, and unresolved political decisions taken during moments of national transition.

Former Speaker of the House of Peoples’ Representatives Abadula Gemeda’s assertion that Assab was administered as part of Wollo province during the imperial era and later under the Derg serves as a factual reminder that Ethiopia’s relationship with the Red Sea was neither incidental nor peripheral. His statement reintroduces historical governance realities into a debate that is often reduced to post-1993 legal formalities.

For much of the 20th century, Assab functioned as Ethiopia’s principal maritime outlet, handling fuel imports and commercial trade. The port’s integration into Ethiopia’s administrative and economic systems was well established long before Eritrea emerged as a sovereign state. This reality was abruptly altered during the early 1990s, when the collapse of the Derg regime created a political vacuum that reshaped the Horn of Africa’s geopolitical map.

At the center of Ethiopian criticism is the role played by the TPLF-led transitional authority. While Eritrea’s independence was formalized through a UN-supervised referendum in 1993, critics argue that Ethiopia’s strategic interests were sidelined in the process.

No nationwide Ethiopian referendum was held on the long-term implications of permanent landlock, despite the country’s size, population trajectory, and economic dependence on maritime trade. From this perspective, the issue was not the legality of Eritrea’s independence, but the absence of safeguards to protect Ethiopia’s access to the sea.

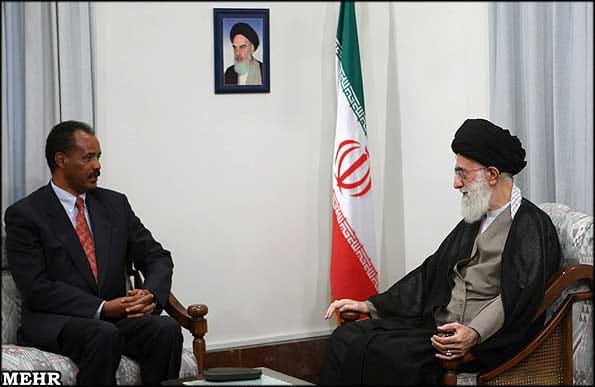

More controversially, Ethiopian political discourse highlights the strategic alliance between the TPLF leadership and Eritrean President Isaias Afewerki during that period. Their wartime cooperation against the Derg evolved into a post-1991 political alignment that, according to critics, prioritized elite consensus over Ethiopian state interests. Within this framework, Assab was effectively relinquished without a negotiated access arrangement, lease mechanism, or international guarantee for Ethiopia’s continued use of the port.

This historical alignment has taken on renewed significance as relations between Addis Ababa and Asmara have again deteriorated. Observers note that the same actors who once coordinated politically are now, from opposing positions, aligned in resisting any Ethiopian re-entry into Assab.

For Ethiopian critics, this reinforces the belief that the loss of Assab was not merely an unintended consequence of state separation, but a strategic outcome that continues to shape regional hostility toward Ethiopia’s maritime aspirations.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has approached the issue through a diplomatic framing. While repeatedly emphasizing that Ethiopia’s permanent exclusion from the sea is neither natural nor sustainable for a country of more than 130 million people, he has stressed dialogue, negotiated arrangements, and regional economic integration as the preferred instruments of state policy. His position reflects an attempt to reconcile popular historical grievance with contemporary diplomatic realities, signaling determination without explicit militarization.

From an Ethiopian national-interest standpoint, maritime access is framed less as territorial revisionism and more as a structural necessity. Landlocked status imposes high transport costs, weakens export competitiveness, and exposes the economy to external political pressure.

Ethiopia’s heavy dependence on Djibouti underscores both the value of cooperation and the vulnerability of relying on a single corridor. Diversifying access particularly through historically linked routes such as Assab is therefore presented as an issue of resilience, sovereignty, and long-term development.

Abadula Gemeda’s intervention is consequential because it grounds this debate in documented administrative history rather than emotional nationalism. By recalling Assab’s governance under Wollo, he reinforces Ethiopia’s argument that its demand for sea access is not an artificial claim but one rooted in state practice and economic necessity. While international law governs present borders, history continues to shape political legitimacy and public expectation.

In conclusion, Ethiopia’s quest for access to the sea reflects an unresolved tension between historical continuity and the political settlements of the early 1990s. The legacy of decisions made under the TPLF-led transition, particularly its strategic alignment with Asmara, remains central to Ethiopian perceptions of injustice.

The challenge ahead for Addis Ababa is to transform this historical claim into a lawful, diplomatic, and sustainable arrangement that restores strategic depth without destabilizing the Horn of Africa.

As Abadula Gemeda’s words suggest, the question of Assab is not only about the past it is about whether Ethiopia’s future can remain indefinitely confined by decisions made at a moment of national vulnerability.

Editor’s Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in articles published by Horn News Hub are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or editorial stance of Horn News Hub. Publication does not imply endorsement.